- Content Hub

- Business Skills

- Strategy Tools

- Core Strategy Tools

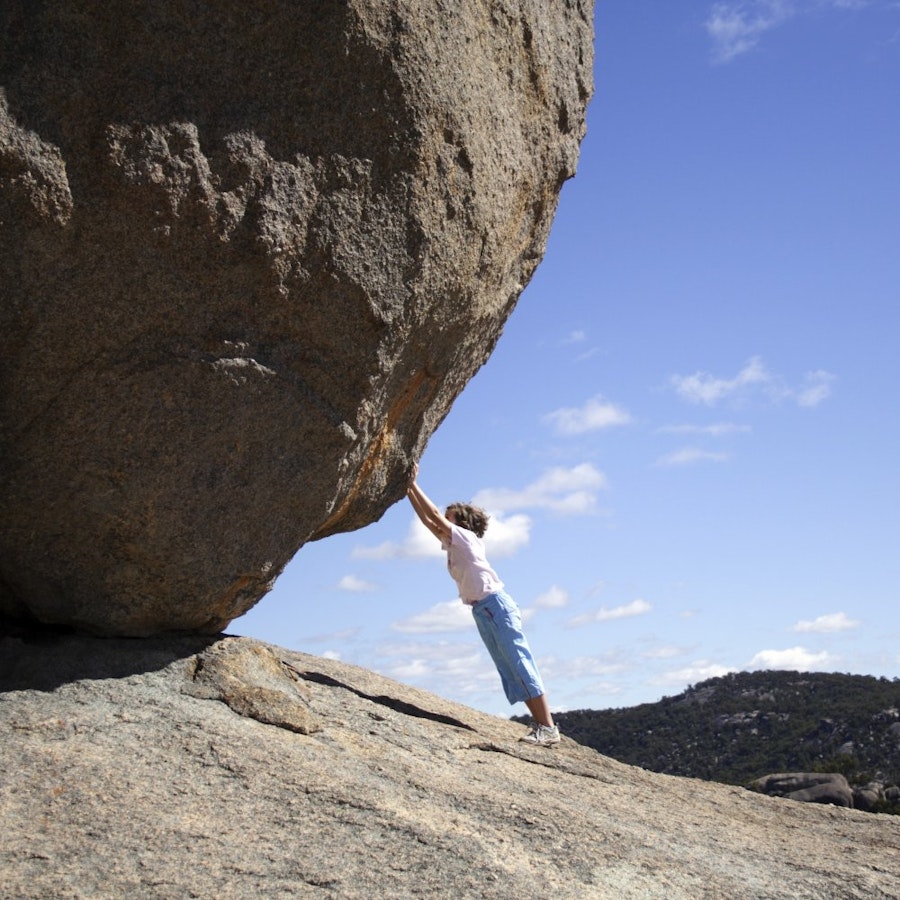

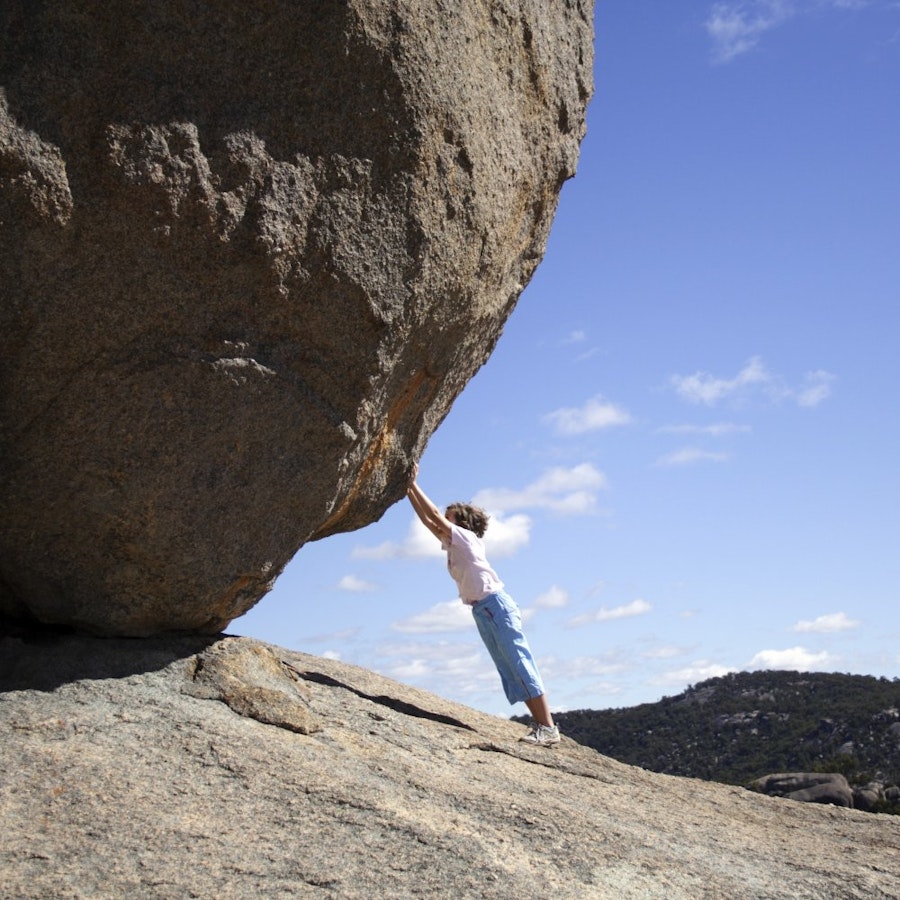

- Think Big, Act Small

Access the essential membership for Modern Managers

Transcript

Welcome to the latest episode of Book Insights from Mind Tools.

In today's podcast, lasting around 15 minutes, we're looking at Think Big, Act Small: How America's Best-Performing Companies Keep the Start-Up Spirit Alive. In it, author Jason Jennings tells us what he learned from extensive interviews with the CEOs of some of the world's most successful companies.

But these aren't the CEOs who grab headlines or grace the covers of typical business books. In fact, you've probably only heard of at most one or two of the nine companies the author profiles – and you might not recognize the names of any of the CEOs. But don't let their low profiles fool you. Other executives might get more attention, but these people quietly and consistently create value for stakeholders. Each leader profiled here has led his company to revenue and profit growth of at least 10% for each of the last ten years – a rare feat.

Their companies operate in a variety of fields – from fast food to sportswear retailing to adult education. Some trade publicly, while others are privately owned. But for all of their differences, the companies do have something in common, the author claims. And that is, their leaders think big and act small.

But what does this mean, exactly? Before we get to that, let's consider who might be interested in this book. Of course, anyone who leads a major company, or who dreams of doing so, will want to snap up a copy. But Think Big, Act Small has broader appeal as well. It helps us understand what makes well-run, effective companies tick – and that's valuable knowledge for anyone when negotiating a volatile jobs market.

So listen up, and see why "swamp water" is a good thing; why it's never worth competing with Wal-Mart; and why good business often means making it up as you go along.

So let's get to exactly what the author means by "think big, act small" – an idea he lays out in the book's short opening section. In essence, thinking big means setting ambitious goals and insisting on excellence in all aspects of the business. Acting small means retaining the flexibility, energy, and work ethic of a startup. Companies that manage to do both excel year after year, in good economic times and bad. The author found that the companies he chose to study all embody the "think big, act small" ethos.

After the opening section, the author gets right to the meat of the book. In a series of tightly argued, compact chapters, he lays out what he calls the "ten building blocks" of creating a successful business – qualities shared by each of the nine companies he's identified. Combined, they form a practical guide for how real-life executives think big and act small.

The first building block is called "down to earth." The author calculates that these nine executives run companies that collectively ring up over US$60bn in sales and employ 130,000 people. Yet unlike some CEOs who made headlines in the late nineteen-nineties, the author's favorite leaders don't insulate themselves from their employees, their customers, or their suppliers. Nor do they scurry after publicity like mice sniffing cheese. Rather, they tend to be modest people who are quite happy to work behind the scenes, away from the media glare.

They see themselves not as cowboys running roughshod over the business landscape, but rather as stewards entrusted to protect and grow the capital under their care. They possess a solid work ethic, promote transparency, and pride themselves on being accessible. The author reports that nearly all of his nine chief executives publicly list their phone numbers in the cities where their companies are headquartered. They aren't afraid that a worker or customer might disturb them at home.

The next building block reinforces the first one. Executives should not only stay "down to earth," but they should also "keep their hands dirty." This can mean something as simple as staying engaged with the company's principal business line. For his main example, the author looks at Jim Goodnight, CEO of a software company called SAS Institute. Starting as a college computer programmer in the nineteen-seventies, Goodnight built SAS into the world's largest privately held software company. Today, the company's products are used by 97 of the top 100 companies in the Fortune 500.

Yet thirty years after founding the company, Goodnight still does what he did at the beginning: he occasionally writes software. This task keeps him intimately in touch with the demands of a fast-changing industry, giving him insights as he makes decisions on the company's broader direction. It also sends a clear message to other employees: If the boss gets his hands dirty by writing code, that means that no one else is too good to pitch in no matter how humble the task. By demonstrating that work ethic transcends position within the company, Goodnight sets a can-do tone that trickles down the hierarchy.

But not every executive will be useful at performing a company's key task. Pattye Moore, for example, is president of Sonic, a fast-food chain. For her, "keep your hands dirty" doesn't mean flipping hamburgers. Such a thing would be a great show, but add little value to the company. Rather, she keeps her hands dirty through regular, meaningful contact with workers, customers, and vendors. This allows her to make marketing decisions that other fast-food executives might miss.

Unlike most of its rivals, Sonic doesn't maintain a test kitchen to concoct new items, which will then be imposed on franchises. Rather, it listens to franchises for ideas, and then spreads them horizontally through the company. One example is a popular beverage called "swamp water," a mixture of every flavor the company sells of a type of frozen drink. Combined, the various flavors become a kind of dark green – hence the name "swamp water." The drink was invented by a customer at one franchise, and now has a national footprint.

The author also features Sonic prominently in his next building block, "Make short-tem goals and long-term horizons." This chapter can be seen as a direct reflection of the "think big, act small" mentality. It reminds us to keep one eye trained on ultimate success, and the other eye monitoring our next steps on the road before us. The chapter details Sonic's turnaround in the mid-nineteen-nineties, when the national brand suffered from wild inconsistency among franchises.

CEO Cliff Hudson turned the company around, largely by doing something conventional: wrestling a measure of control from the franchises and centralizing it at the head office. Some executives might have followed that move by bringing the franchises firmly under heel and ramping up new-store openings, in hopes of selling the company off. But Hudson resisted that temptation. Instead, he continued listening to and responding to the franchisees, and focused on improving sales in existing stores by instituting a series of ambitious but reachable targets. Now Sonic is growing at the rate of some 200 stores per year, and its sales and profits are growing faster than those of its fast-food peers.

The next chapter emphasizes the need for flexibility. Its title says it all: "Let go." And "letting go" sometimes means abandoning success. To illustrate this concept, the author turns to wildly successful sporting-goods retailer Cabela. That company started out mainly in the mail-order business, and by the early eighties had already passed the US$100 million mark in revenue, and established itself as the world's biggest sporting-goods retailer. Yet at a marketing conference, an expert criticized the company's slogan, printed on each page of their catalogs. The slogan went, "quality, service, price, and satisfaction guaranteed." The problem with that slogan, the consultant said, was that "everybody says it, but no one believes it."

An executive committed to "acting big" would have ignored the criticism. But CEO Dennis Highby thought long and hard about the criticism, and, decided to act small instead. Rather than highlight qualities that any company can claim, he decided, the company should boast of its scale. The new slogan became, "world's foremost outfitter."

The next building block to success involves convincing everyone in the company to "think like an owner." To illustrate that point, the author turns to Koch Industries, the second-largest privately held company in the United States. Koch is a large and sprawling company, composed of 13 business lines with total annual revenues in excess of US$50bn.

Yet company owner Charles Koch thinks small by giving each unit tremendous power to make decisions. In Koch's "bottom up" management style, "decision rights" rest with the people who have the best knowledge and information to figure out the way forward. And the company's pay structure reflects this spirit. Compensation directly reflects value created, an arrangement that encourages employees to behave like entrepreneurs running their own businesses. Thus division leaders reap the rewards of their decisions – or pay the consequences – through their paychecks.

The role of corporate headquarters in such an arrangement is to constantly monitor the performance of all the divisions and decide each year whether to hold them steady, invest more capital in them, or sell them. So far, Koch Industries has been extremely successful at "acting small" as it has grown big. In fact, since 1960, its book value has grown at twice the rate of General Electric!

The next building block involves "inventing new businesses." That's typically a task for a startup company, whose owners see an emerging niche and scramble to fill it. But the author argues that successful, established companies can do it as well – provided that they remain committed to "acting small."

The example here is Dot Foods, which started as a supplier of powdered milk to two small-scale ice cream makers in the Midwest. After a while, the dairy market consolidated rapidly, and it was no longer profitable for Dot to focus on a single product in a single industry.

But Pat Tracy, son of the company founder, returned home from earning an MBA with a new idea. At the time, distribution in the growing processed food industry was fragmented and inefficient. Supermarkets bought directly from large manufacturers, and had to place huge minimum orders to get what they wanted, making inventory management a challenge.

Tracy decided that Dot could add value by serving as a middle-man between the manufacturers and the retailers, maintaining a broad centralized inventory and delivering to supermarkets on demand. Predictably, both retailers and manufacturers initially resisted the rise of a profit-taking intermediary, but both sides eventually came to see the value of Dot's proposition.

Today, Dot dominates the food redistribution market – a business it essentially created. And the former powdered-milk provider's annual sales now exceed five billion dollars.

Dot's story could just as easily have been used to illustrate the next building block: create "win-win situations." In today's business environment, many companies thrive by selling as much product as they can, thinking only of the next quarterly report. But smart companies plan for long-term success by selling not products but rather solutions.

One company that embodies this ideal is Medline, which manufactures and sells supplies to the medical industry. At a time when the healthcare industry is being forced to cut costs, Medline presents itself as a solution provider. Here's how it works. Say a hospital needs to cut 10% from its budget of necessary items like patient gowns and nurses' uniforms. Rather than merely offer a line of goods, Medline offers the service of supplying the hospital's needs. It offers to meet the hospital's cost-cutting targets, and pay a penalty if it can't. If it exceeds the cost-cutting targets, it gets a bonus.

In that arrangement, what might be an adversarial relationship turns co-operative, and the seller and the buyer can begin planning together for the long term. That, the author says, is how a company survives and thrives in an industry marked by cost-cutting.

The next building block involves carefully choosing competitors. No startup company would choose to go head to head with a giant like Wal-Mart, and nor should any established company that hopes to survive in the long haul. That's the lesson the author draws from Petco, a retailer catering to indulgent pet owners.

Company chairman Brian Devine had helped build another specialty retailer, Toys R Us, into a giant in the 1980s. After leaving the firm, Devine watched as Toys R Us unraveled as a company. Its customers simply abandoned it for Wal-Mart, where they could find essentially the same products for lower prices. When he stepped in to take the helm of Petco a decade ago, it was an ailing pet shop chain with declining sales and mounting competition from Wal-Mart. Devine quickly invested in the stores, making them attractive and welcoming places for pets and their owners.

And he focused on high-quality specialty items that would appeal to discerning shoppers, as well as having his buyers abandon any product that was widely available at Wal-Mart. The result has been a revived Petco, with robust annual profit growth and sales now exceeding US$2bn.

The author's next commandment is to "build communities." His main example is Strayer Education, a supplier of education services to adults. However, he seems to lose his way a little here. He compellingly tells the story of Strayer's rise from humble beginnings to a US$2bn company, but doesn't precisely tie its success to community building. Mostly, what propels the company is the hard-driving spirit of its CEO, Ron Bailey, who bought it in the 1980s by mortgaging his own house. Bailey does embody another one of the author's principles, though: He "gets his hands dirty" by continuing to teach classes.

The final building block is "grow future leaders." To do so, the author argues, large companies have to behave like family businesses grooming the next generation to take over. Leadership nurtured within a strong, vibrant culture is more likely to take a company to the next level than some "savior" from the outside. To illustrate this principle, he turns to O'Reilly Auto Parts, a family business that has morphed into one of the largest auto parts retailers in the United States.

As O'Reilly has grown into a giant, the company's founders have consciously maintained the organization's family feel. They promote from within at the store level, as well as at the corporate level, and make it every manager's responsibility to identify and train his or her successor. As a result, the company has one of the lowest turnover rates in a high-turnover industry.

By the book's end, the readers walk away convinced by the author's central message. In a business world increasingly dominated by giants, it's essential to "think big." And to avoid being steamrolled by them, it's just as important to be nimble – that is, to "act small."

Think big, Act Small by Jason Jennings is published in hardback by Portfolio.

That's the end of this episode of Book Insights.