- Content Hub

- Leadership and Management

- Change Management

- Understanding Change Management

- Continuous Improvement for Ongoing Change

Access the essential membership for Modern Managers

Change is usually seen as a finite process, with a beginning, middle and end, but what happens when the transformation is complete? In many cases, team members go back to a ‘business as usual’ approach and old habits return. Yet effective organizations are able to avoid this by encouraging a culture of continuous improvement (CI).

This is the belief that an organization can never be ‘perfect’, and that there will always be better ways of doing things. Some advocates of CI even argue that organizations no longer compete on how effective their processes are, but on their ability to continually improve them. [1]This article will outline the some of the most common approaches to CI, when it should be used and how to avoid some of its limitations.

What is CI?

CI is defined as:

"A systematic effort to seek out and apply new ways of doing work i.e. actively and repeatedly making process improvements." [2]

It is not a sweeping transformation and it does not require a massive input of capital. Instead, it is the everyday ideas from throughout an organization that can improve productivity, efficiency, quality and delivery.

Where CI is implemented effectively, it becomes a part of an organization’s culture, whereby every employee is encouraged to think of small improvements on a daily basis.

For example, at one Toyota US plant, managers claimed to have received over 75,000 suggestions from 7,000 employees in a one year period. 99% of those ideas were implemented. [3]

History

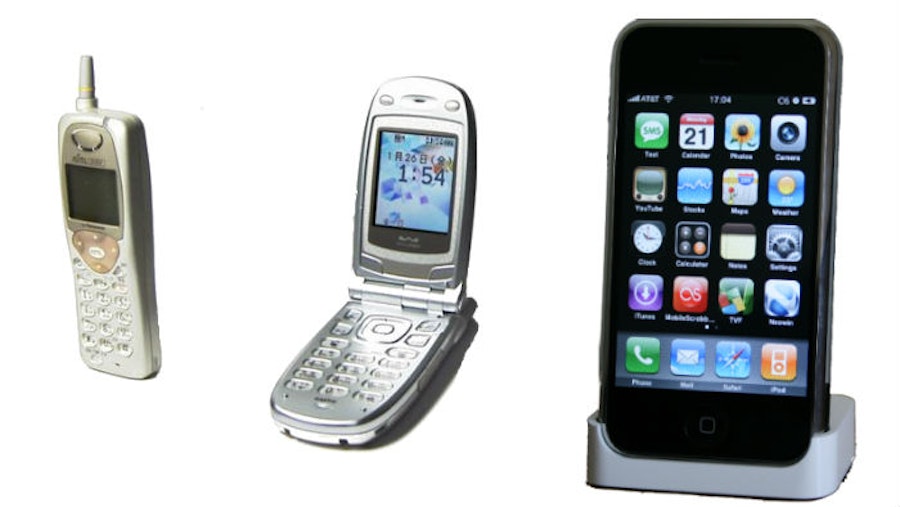

CI has its origins in the work of American statistician Dr W. Edwards Deming, who spent the Second World War teaching quality control methods to US manufacturers. [4] Then, in 1947 and 1950, Deming traveled to Japan as part of a group tasked with rebuilding the country’s industry.

Deming’s approach to process improvement became known in Japan as ‘Kaizen’; literally ‘change for the better’. [5] Organizations that use Kaizen encourage their employees to suggest small improvements on a continuous basis.

Over the next 30 years, Japanese manufacturing experienced huge success in the automobile, telecommunication and consumer electronic markets, until eventually the benefits of Kaizen were impossible to ignore. [6]

Western manufacturers then began to adopt CI as an essential part of their organization’s activities, and today it has become common practice around the world.

Comparison with Change Management

CI is not a tool that can be used to change an organization quickly. The table below demonstrates how it differs from change management:

Change management

Big changes

High cost

Fixed-term event

Ideas come mostly from senior management

Continuous improvement

Small changes

Low cost

On-going activity

Ideas come mostly from employees

Not all of these points are true for every change process, but they do reflect the main differences between the two approaches: change management is ideal when transformation is needed; CI is best used as an everyday philosophy.

Some of the most popular approaches to CI are outlined below.

Six Sigma

Six Sigma is a data-driven approach to CI that aims to eliminate almost all defects from a product or process. It became popular after General Electric CEO Jack Welch championed its use across the organization in the mid-1990s, during a period of enormous growth for the company. [7]

Six Sigma is different from Kaizen in that it is not based on employee suggestions. Instead, every defect is recorded and the data analyzed to identify where it occurred and how it can be eliminated in future. For a process to be acceptable, it cannot produce more than 3.4 defects per million ‘opportunities’ for a defect to occur.

Opportunities for a single part might include form, fit and function. [8]

Lean

Lean production is a form of CI that focuses on eliminating waste. Organizations that use Lean do so to reduce costs and shorten the time between customer order and ship date.

Like Kaizen, it is people-driven in that employees from throughout the organization are encouraged to focus on efficiency and suggest improvements. At the same time, it is a response to the main needs of an organization’s customers: high quality, low cost and short delivery times. [9]

ISO 9001

ISO 9001 is an internationally recognized quality management standard that indicates an organization has met certain requirements that benefit its customers. Among these is the requirement for ‘Continual Improvement’. [10][11]

While not strictly speaking a form of CI in itself, ISO 9001 does encourage organizations to develop products and processes that are not just acceptable but exceed the expectations of the organization and its customers. ISO 9001 accreditation also requires documented evidence of continual improvement, so is useful to ensure that improvements are objectively measured.

The EFQM Excellence Model

The European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) Excellence Model is an approach to Total Quality Management (TQM) that focuses on delivering 'excellence'. It splits an organization into 'enablers’ that describe its actions, and ‘results’ that describe the impact that it has.

By improving the enablers, better results can be achieved. By learning from the results, further suggestions for improvements can be made, and so on.

Integrating CI

Some of these methods, like Six Sigma, require that CI be implemented formally, such that every process is analyzed to identify areas for improvement.

Less formal processes, like Kaizen or Lean, require more of a cultural shift, whereby senior management encourages CI as part of the organization’s core values.This can be done in a number of ways. For example:

- posters in public areas (canteens, toilets, staff rooms)

- workshops

- email campaigns

- notices on the organization’s intranet

Yet it is even more crucial that employees feel they can make suggestions to their manager that will be taken seriously. A CEO who emphasizes this to their senior management team can start a chain reaction, whereby the senior managers pass on this philosophy to their department heads, and so on.

One famous advocate of this approach is Jack Welch. Every year he would gather GE’s top 500 executives and outline his broad ideas for the business. These executives would then host similar events for their direct reports, until the message had reached GE employees around the world. [12]

Identifying Improvements

Ideas for improvements can come from a range of sources, but most commonly it is the front-line employees who will notice areas of waste or opportunities for greater efficiency.

One way to gather employee suggestions is the 'suggestion box', a technique made famous by Toyota when in 1951 they launched the 'Toyota Creative Ideas and Suggestions System' (TCISS). [13]

Incentives were used to encourage participation and, as a measure of its success, the TCISS has continually improved over time so that it now includes teams tasked with creating new ideas.

Toyota also notes that the quality of employee ideas has improved over time, and write that:

“This Kaizen (CI) Spirit has continued to develop over the years and is deeply embedded in Toyota's culture, not only in production but also in sales operations around the globe.” [15]

Other ideas may come from customers or suppliers, as positive feedback and complaints can both lead to improvements.

Where more rigid approaches to CI are chosen, the techniques used to identify improvements are often statistical. See the article on Improvement Tools for more on this.

Barriers to CI

Despite the benefits of CI, implementing such a scheme is not easy. Often senior management will be flooded with too many ideas at once, and cannot act on them all because it would be too complicated or too expensive. In these cases, CI is sometimes abandoned and seen by employees as a passing ‘fad’. [16]

Therefore, senior management must take care to prioritize ideas by:

- considering how easy the idea will be to implement

- assessing the likely benefits of the idea

- agreeing on how success will be measured (fewer defects, improved sales, etc)

It can help to speak to employees whose ideas have been given low priority, or been rejected, to emphasize that they have not been ignored. This helps overcome another barrier to CI: lack of employee engagement.

If employees feel that their ideas are not being considered, they are likely to stop making suggestions. This can be addressed by listening to new ideas, thanking employees for their suggestions and giving an appropriate response.

Larger organizations can find it particularly difficult to implement CI because processes are often highly structured and difficult to change. However, this problem can be treated as an opportunity to trial new ideas.

Where a process is carried out in two or more separate locations, the impact of making a change at one location can easily be measured. If it is successful, it can then be rolled out across the wider organization.

Criticisms of CI

Although CI is widely regarded as key to an organization’s long-term effectiveness, the way it is handled has been criticized for years.

As far back as 1998 there were those at GE who thought that Six Sigma was introducing bureaucracy into a system that was already highly efficient. [17]

When GE executive James McNerney took over at 3M, those same criticisms followed him. He implemented Six Sigma and made the organization far more efficient, but not without sacrificing the creativity that 3M was famous for. [18] That trend is now being reversed, in part by reducing the rigidity of the company’s approach.

This suggests, however, that CI is not as appropriate in a research or design environment as it is in manufacturing. [19]

Another criticism of CI is that it limits options. Where employees are constantly encouraged to improve processes, they often fail to ask themselves whether the process is even necessary. Consultant Ron Ashkenas offers the example of a Six Sigma team tasked with improving the data flow from a company’s headquarters to its field offices. Once they took a step back, they realized that much of the data was unnecessary and they could divert their attention to other concerns. [20]

Finally, leaders who implement CI should consider its impact on their organization’s culture. For example, an organization that takes a data-driven approach may cut itself off from the ideas of employees. Conversely, an organization that encourages the sharing ideas should not underestimate the importance of data. Ultimately, it is best to take a balanced approach and not let CI restrict the organization in any way.

Conclusion

In essence, CI is most effective when it is introduced in a nuanced way. It will not transform an organization quickly, but neither should it limit the organization’s capacity to innovate.

What it can do is gradually make an organization better, by making small changes to existing products, processes and services, to make them more effective.

Ultimately, the CI approach itself can always be improved, as it has been at Toyota and 3M, and leaders should regularly assess whether it is generating the results they desire.

Visit the Continuous Improvement topic for more on this subject.